The start of a new decade in the design world brings with it a growing focus on inclusive design. This means that UX professionals across the tech industry are drawn increasingly to create products and experiences that are truly inclusive.

If you’re new to the world of UX design, don’t assume that inclusive design is an “advanced topic”! In reality, inclusion is at the heart of the history of UX design. Whether you’re designing a login screen, a search experience, a purchasing process, or anything else you can imagine—if your users feel excluded from the experience, they’re likely to drop out of it entirely.

Inclusive design is one of the most impactful and effective ways improve experiences for users of any identity, background, or experience.

But what is inclusive design? What’s involved in going beyond mere accessibility to making your app or website truly inclusive? In this guide, I’ll explain what inclusive design is and outline the primary implications of inclusive design for digital products.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

- What inclusive design is and why it matters

- The 2 most essential elements for inclusive design

- Inclusive design embraces accessibility standards

- Going beyond accessibility: Inclusive design best practices

- A final word

1. What inclusive design is and why it matters

In short, inclusive design is the practice of intentionally including the needs of users who likely experience exclusion in many aspects of their daily lives due to being part of an oppressed group or a statistical minority. If we don’t intentionally include the risk is to unintentionally exclude.

As a UX professional (aspiring, new, or seasoned), you hold the power to shape things—to alter the nature and direction of a project. That is a tremendous responsibility, and it means that you have the ability to influence design decisions in ways that benefit people who are often overlooked or ignored.

In fact, everyone contributing to the design of a digital product—the UXers, of course, but also software developers, product managers, and even talent acquisition professionals—is responsible for the social impact of the solutions they deliver, for the decisions they make and for those they choose not (or forget) to make. This is why understanding the scope and complexity of inclusive design is essential for aspiring tech professionals.

If we don’t intentionally include the risk is to unintentionally exclude.

People with disabilities, oppressed minorities, and potentially any user (ourselves included) can and do experience exclusion when interacting with a digital product. Negative, exclusionary, and discriminatory user experiences come in many forms, including:

- Denied access

- Identity demeaning experiences

- Unwanted exposure of sensitive information (real or perceived)

- Frustrating experiences

Taking this into consideration, one way we can define an inclusive design approach is to say that it should enable the delivery of solutions that are not just easy to access, but also make people feel welcomed, safe, and valued.

2. The 2 most essential elements for inclusive design

Inclusive design happens when you have 1) the right team behind the design decisions and 2) user involvement in the design process. Let’s break down what these two foundational elements are all about.

The right team

Whether it’s conscious or not, we’re all biased. The human tendency is to imagine that others have experiences similar to our own.

This is a tendency that needs some time, intention, and exposure to people’s stories and experiences that are different from our own to change. How does this impact the design process? It means that we are often unaware of who we are leaving out of the design process.

The identities represented within a team have a huge impact on what decisions are made. As Mike Monteiro says in Ruined by Design,“All the white boys in the room, even with the best of intentions, will only ever know what it’s like to make decisions as a white boy.”

Having diverse teams helps us notice and overcome our individual biases. A product design team made up of people with different cultural backgrounds, varying abilities, and different gender identities is more powerful than a team of people who look, behave, identify, and think in the same ways. So find ways to build a diverse team that’s capable of noticing and designing solutions for a broader range of user needs.

Involving users

UX is based on the belief that users should be the primary stakeholder, at the center of everything we do as we shape products and solutions for them.

Maybe you’ve heard it before: interview users, discover their needs, test ideas with them, and listen to them once you have delivered your solution(s).

Contact with users becomes even more necessary when designing for user groups we don’t know. Design and accessibility expert Kat Holmes talks about designing with users as an essential part of the process. If we want to make sure that the experience we design delivers value to everyone who might benefit from it, we need to design with excluded communities rather than for them.

Here is where collaborative design methods and tools such as co-creation workshops and sacrificial concepts become useful.

3. Inclusive design embraces accessibility standards

Often, when talking about inclusive design, the first (and sometimes only) association that people/organizations make is with accessibility. Accessibility refers to the design of products, devices, services, or environments that are usable by people with disabilities. While inclusive design goes beyond accessibility concerns, designing for accessibility is an integral part of designing for inclusion.

When designing websites, there are some well-known standards and guidelines you can follow to ensure that you’re not excluding users on the basis of ability—the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) is a great place to start.

Accessibility should be integrated fully into your inclusive design processes. Companies like Google have integrated accessibility principles seamlessly into their design language. Here’s an example of how Material Design has seamlessly woven accessibility standards into Google’s design language.

![]()

4. Going beyond accessibility: Inclusive design best practices

Inclusive design embraces accessibility, ensuring that users are not excluded because of their abilities; it extends that same effort and intention to the needs of users who are often excluded for other reasons (age, background, race, gender identity, etc.). Here are four key considerations and best practices to help you design more inclusively.

Note that the examples that follow are based on experiences and screenshots taken between November 2019 and January 2020. I don’t include them to portray any company or product in a negative light—only to give some practical, real-world examples of where inclusive design can be applied.

Who knows? Maybe these examples will start a conversation with these or other companies about how to design more inclusively!

Use inclusive imagery

Representing people through icons, illustrations, and photographs requires thoughtfulness.

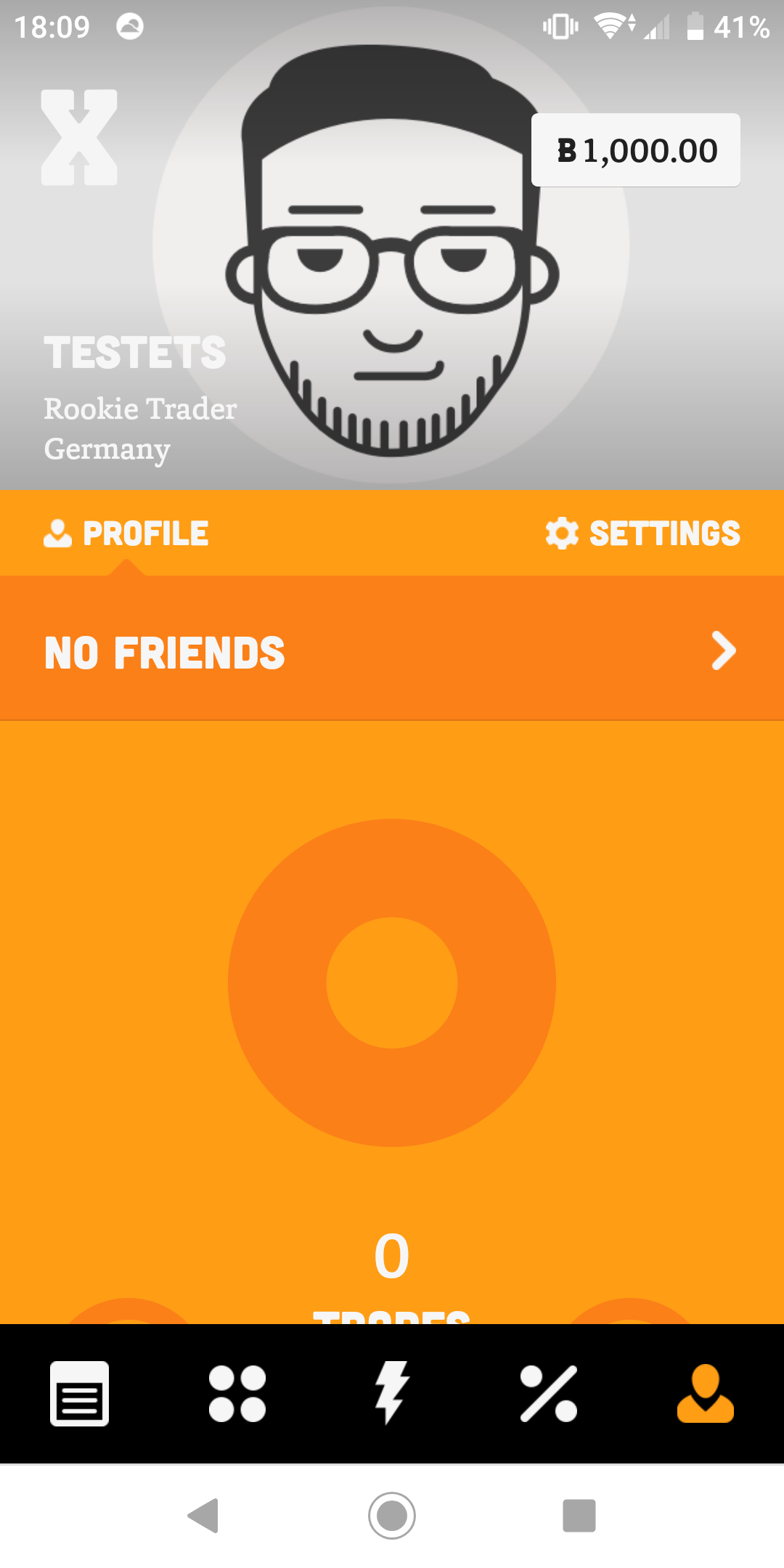

The stock trading app BUX assigns a default profile image to all new users. It depicts a person with features that are stereotypically considered to be “male”: broader facial features, eyes without lashes, facial hair, etc. Because so many of us are culturally conditioned to associating the default male features with being healthy, able, white, etc., the message this sends to their users is: our users are capable, smart, financially savvy—and male. Regardless of what their actual or ideal user base looks like, chances are high that some portion of BUX’s users will not feel like this image is a good representation of them. If we want to be inclusive, there are better choices for a profile picture placeholder.

There are two strategies to produce inclusive images: abstracting and diversifying. Neither take a great deal of effort and both can only help more users feel more included in the experiences and products you design.

Abstracting

Abstracting means departing from a realistic, detailed representation in favor of something that allows users to fit the image into their own lives and identities. You can accomplish this by using more conceptual but still human-like illustrations—or even objects or animals.

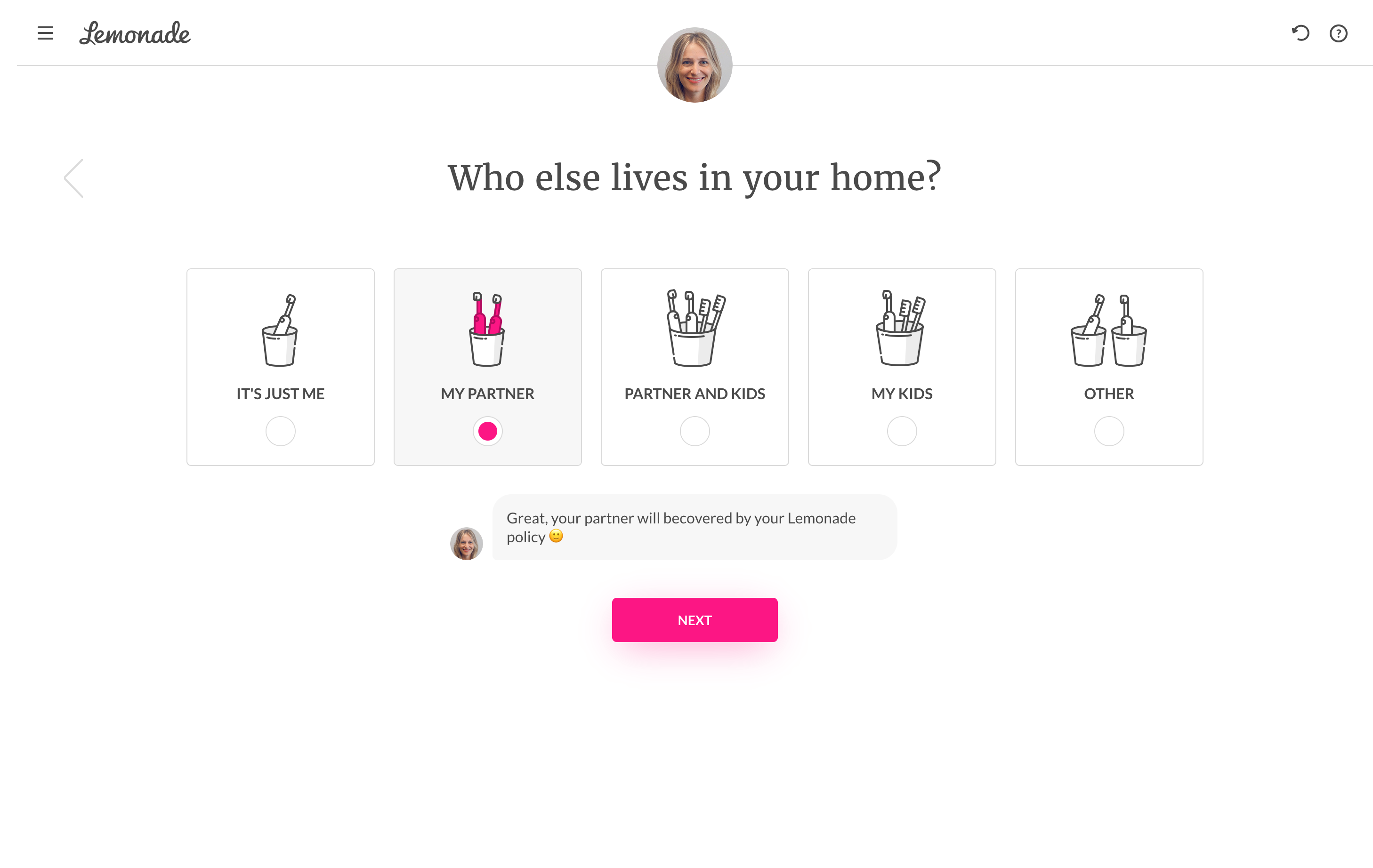

Abstracting is a great way to ensure our users will not feel excluded. The same is true when we want to represent not just one user, but a group of people who are known to them. Lemonade does a great job of this when a new user signs up for their services.

Toothbrushes are comparatively free of implications regarding users’ background, gender identity, or abilities. The illustrations and accompanying text both allow users to select a response to the question without making assumptions about the users themselves.

Diversifying

Diversifying, on the other hand, aims to represent the multitude of differences users might identify with. This strategy has been employed a lot already in advertising and is suitable for marketing websites as well as in-product imagery that doesn’t act as a direct representation of an actual user or a person they know.

When you diversify, you seek to represent the full spectrum of humanity in any imagery you use. Airbnb’s illustrations are a fantastic example of this. They’re delightful and they aim at reflecting the differences in their community.

Inclusive imagery requires good collaboration between UX and UI designers. Learn more here: How Do UX and UI Designers Work Together?

Write inclusive copy

Inclusive copy is all about making words work for everyone. Words are as powerful as images—or even more so. We use words to consume information, to communicate with others, and to define and express our identity. To start making your copy more inclusive, make sure to use easy language, be attentive to the words you use in forms, and write notifications wisely and consistently. One of the most common misuses of this is the practice of “click here” links.

Easy language

Using simple words and short sentences is inclusive. This makes information more easily accessible for everyone. Complicated, infrequently used terms and endless paragraphs make things unnecessarily difficult for people with cognitive disabilities and for people that are not fluent in the language of your interface.

Forms

Forms designed to collect sensitive user data such as name, gender, age, etc., are still an often neglected touchpoint in terms of helping users to feel included. Here, the power and duty of the designer is that of deciding:

- Whether or not a specific question needs to be asked in the first place

- How to ask the question

- What answers to make available for users to select from

For example, let’s think of a form with a field inquiring about users’ “sex.” Before you finalize the copy, ask yourself:

- Why do we want to ask users about their sex?

- Is it necessary for us to know this?

- What do we want to do with that information?

If you conclude that there’s a good reason to ask this particular question, then reflect on how to ask the question. As you do this, take time to consider: Sex and gender are two very different things. Is it really sex that you need to know? Or is it their gender, or something else? Do you need to know what they identify with or what is on their passport?

Now, back to your form. You might list all suitable answers to this question or you might allow users to type in their answer in an open text field (or some combination of these two). Be mindful of the options you make available for users to select and make sure they are in keeping with the information you’re actually asking for.

Finally, this is an incredibly personal question for some people—consider explaining to users why you are asking and how the information will be used.

You can take a similar approach to questions about ethnicity. Just like gender, it’s a complex topic and people might define themselves using more than one word. Showing a limited set of mutually exclusive options can make them feel pretty bad (and remember that race and ethnicity don’t mean the same thing).

Notifications

Copy is everywhere, so it’s easy to forget about applying inclusive copywriting guidelines to some touchpoints. Notifications are a critical space for communication, because they speak directly to the user, and sometimes they speak to other people about the user.

To continue along the sex/gender thread, let’s look at how one dating app approaches gendered language.

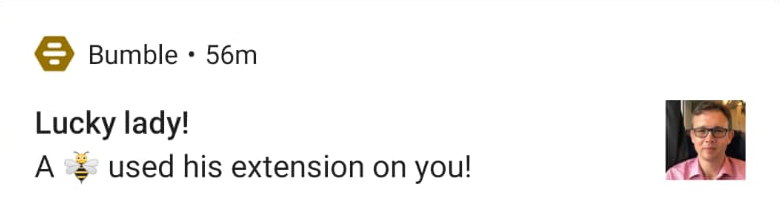

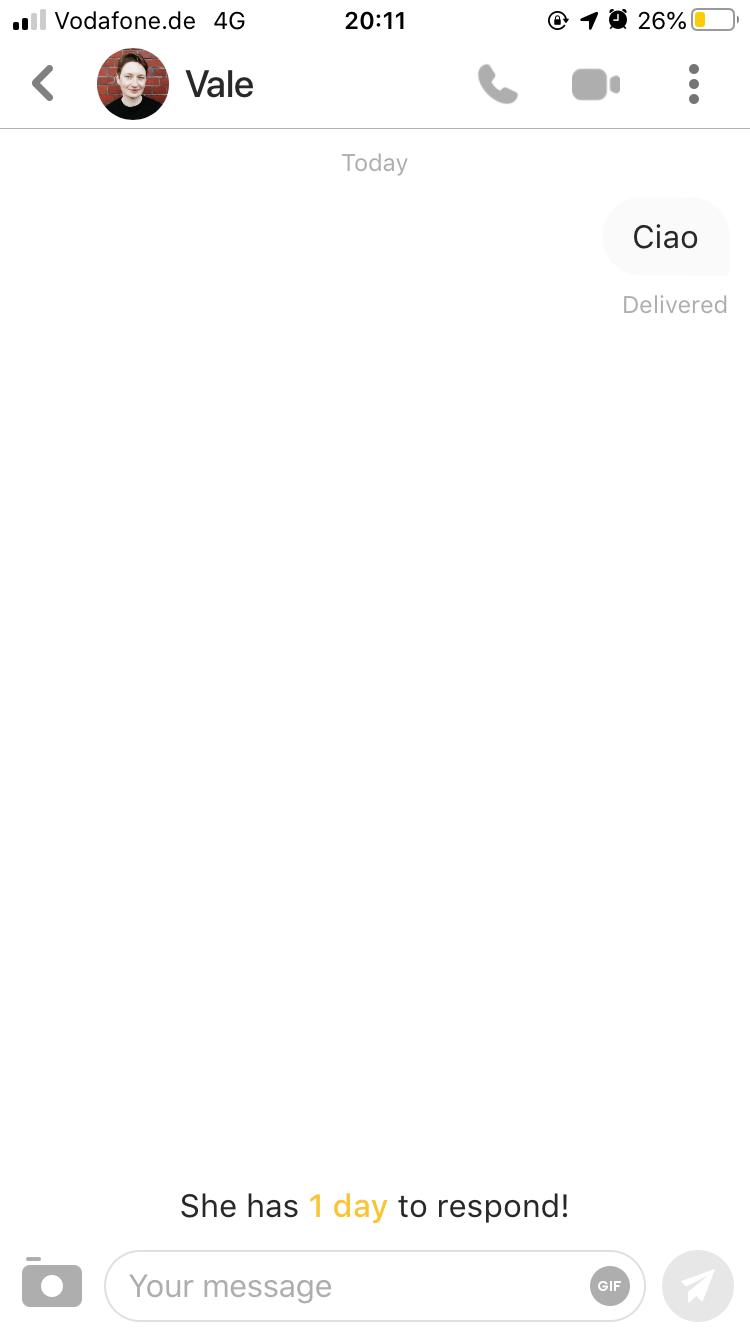

Bumble allows users to select their gender outside of the binary (male/female)—which is great, but it’s far from enough to call it a truly inclusive experience. Instead of asking users to specify their pronouns, the dating app assigns pronouns and uses them to communicate with matches. It also uses gendered words when addressing users through notifications.

Even though I have selected “genderqueer” under gender identity and opted to have Bumble display my gender identity on my profile, the app still uses gendered language when addressing me (“Lucky lady!“)and talking about a match (“his”).

The app also uses the wrong pronoun when notifying my matches about me (“she”).

If the app allowed users to specify their own pronouns, users would feel more included and more accurately perceived and represented.

Providing a more fully personalized experience would fix this problem, provide a more customized experience, and build stronger rapport with all users. Another solution would be to get rid of pronouns and gendered language altogether. This approach would be less personal, of course, but more scalable.

Note: Many inclusive copy issues are also addressed with some general UX writing best practices.

Considerations for voice user interfaces

Alexa, Siri, Google Assistant. These voice user interfaces all feature default female-sounding voices in pretty much all languages (and sometimes don’t have alternatives).

This is not a coincidence! We live in a culture that tells us that women are more obedient, supportive, desirable assistants than men, and that is reflected from the research to the voice personas and on into the product experience itself.

Culture affects everything in UX. Accents trigger certain associations with race, culture, socioeconomic status, etc. While we cannot escape this, it’s up to us to choose to iterate on existing stereotypes or not. Google Assistant does a great job of this as it names its various voice options after colors, rather than nationality and sex.

![Example from Google Assistant The different voice options for Google Assistant are named after colors instead of using the [nationality]+sex formula used for the naming of Siri’s voices.](https://d3mm2s9r15iqcv.cloudfront.net/en/wp-content/uploads/old-blog-uploads/google-assistant-purple-voice.png)

Define your own inclusive design principles

Design principles are a set of rules and considerations that help teams and individuals make design decisions. They state intentions, provide references, and create a united vision and shared standard for team members.

Part of your job as a designer is to define and adopt design principles specific to the company and the products you’re designing. If you want your team to take an inclusive design approach, you need to embed inclusivity into the design principles that guide your efforts. Let’s consider some examples to give you an idea of what these principles might look like.

The key principle n°1 of The Designing for Children Guide is, “Everyone can use.” This type of principle is useful for aligning the whole team and guiding strategic decisions related to what is going to be designed. But inclusive design principles can also translate into detailed guidelines that facilitate execution—how things will be designed.

For example, the GOV.uk design system provides a clear pattern for how to ask users about their ethnic groups: ask in two steps. According to GOV.uk’s pattern, designers should ask the broad ethnic group first (“Asian or Asian British,” “Black, African, Black British or Caribbean,” etc.), followed by a more specific set of options determined by the broad selection the user makes.

On the level of specific user interface designs, Salesforce’s accessible mobile design guidelines prescribe that, “Every custom gesture should have a one-finger equivalent, so users with limited motor capabilities can use it.”

Finally, Microsoft is a classic example of a company that strives to design according to principles driven by inclusivity (and especially accessibility). Their inclusive design toolkit includes extensive resources on how to design inclusively—including detailed instructions on how to use persona spectrums in your design work.

To learn more about design principles in general, check out these two articles:

- Affordances, signifiers, and feedback: What they are and why they matter

- 10 UX principles that will change the way you see the world

- 7 Universal design principles to make your designs more inclusive

(Note that affordances are a fundamental concept in UX design, and one of the first and most basic ways to address inclusion and accessibility.)

5. A final word

The time to start designing for inclusivity is now. Inclusive design is a thriving area of focus where new designers can have a lot of impact at many different levels.

At a career level, we can say that the ability to think about inclusion and advocate for it is becoming an increasingly attractive skill to employers across the industry. Having knowledge and experience (and deliverables in your UX design portfolio!) in inclusive design will set you apart from the application to the interview.

Because best practices are still being shaped, the opportunity to have an impact at an organization or industry level is huge. Don’t wait to be told you need to up your design game with inclusive practices—join the conversation and lead the charge!

Finally, what you produce as a designer has the potential to impact individual lives in deeply meaningful ways and to influence the culture around you.

The spotlight is already shining on inclusion. The more intention we place on inclusive design, and the more attention we give it in our conversations and design processes, the more usable our products and experiences will become and the greater the impact our work will have.

If you’d like to learn more about UX design and inclusion, check out these articles: