User personas and Jobs-To-Be-Done are two common approaches taken to user-centered design—and there is some debate about which of these approaches is the most effective.

Earlier this year, UX pro Jared Spool called Jobs-To-Be-Done an “occasionally useful gimmick.” This sparked further discussion on Medium and Twitter (we’ll spare you the drama), which essentially boiled down to which of these approaches is useless and which one actually accomplishes something.

Does it have to be a battle? Maybe not. Let’s take a step back and break both of these approaches down to understand what they look like, how they’re different, and what they share. This guide will cover the basic elements of user personas and Jobs-To-Be-Done, as well as their pros and cons. We’ll also discuss how to blend the best aspects of both to achieve a superior strategy.

Here’s what we’ll look at:

- What is a User Persona?

- What is Jobs-To-Be-Done?

- Personas vs. JTBD: Which to use?

- A blended approach to Personas and JTBD

1. What is a User Persona?

A user persona, done well, is not merely the profile of a fictional user. It isn’t a random collection of information transformed into a fictitious character that embodies your biases. Rather, a user persona is a thoroughly researched aggregate representation of people who actually use your product (or who you’d like to use your product). Ideally, you’ll use more than one persona—and you might even consider exploring persona spectrums to ensure that your design decisions are accessible and inclusive of all your users.

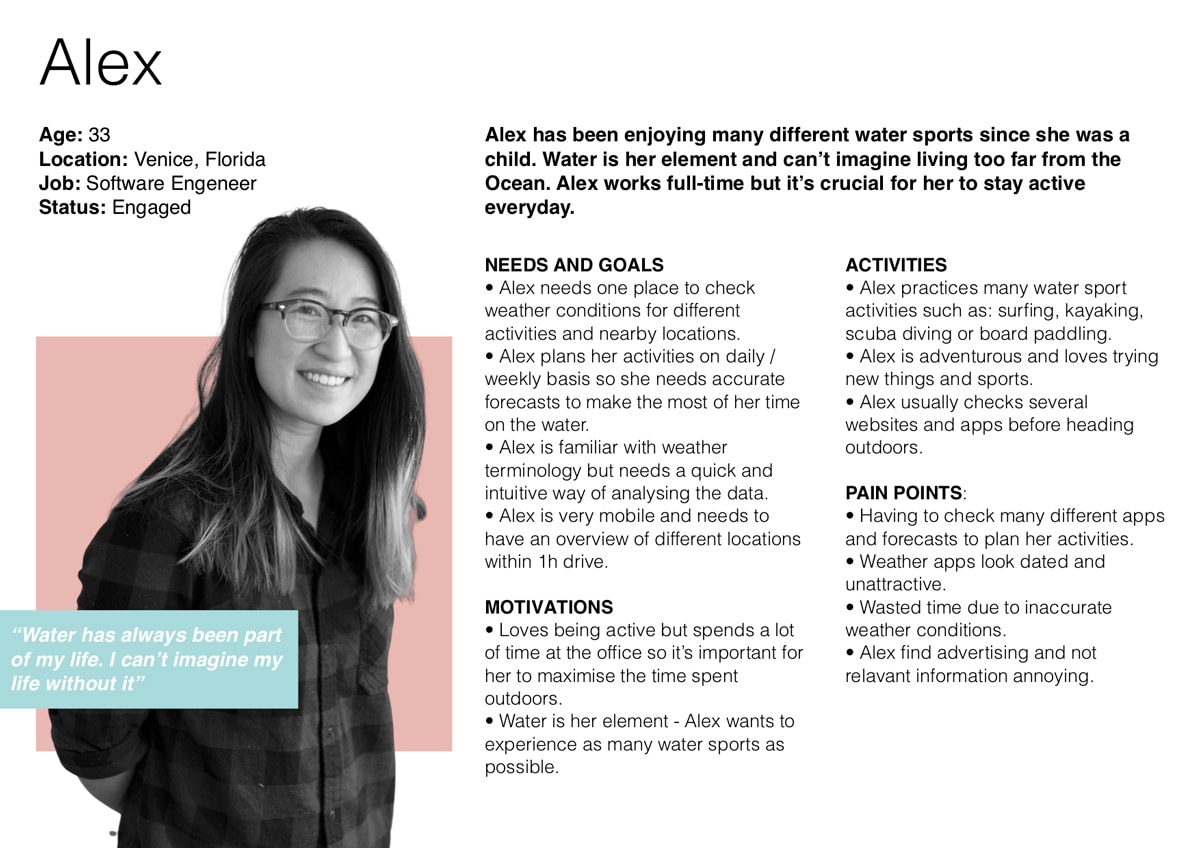

Here’s an example of what a user persona looks like:

Here we have an image that represents a user, along with relevant demographic information, a summary of the user’s situation needs, goals, activities, motivations, and pain points as they relate to the product.

User personas keep your users as the ultimate focal point as you go about identifying pain points along the user journey and defining the design problems you will solve.

Personas set the starting point for your design process at the person or people you are designing for. They also help to generate empathy with the people involved in designing, producing, and marketing your product.

2. What is Jobs-To-Be-Done?

Jobs-To-Be-Done (JTBD) shifts the focus from a hypothetical or aggregate user to what your actual users want to accomplish by using your product.

This approach sets the starting point for your design process at the job your users want your product to accomplish. Rather than creating a representation of your users, you ask what job your customers are “hiring” your product to accomplish. A JTBD approach starts by asking, “What do our users really want?”

Unlike user personas, JTBD doesn’t have a defined process or specific artifacts that will uniformly result from its implementation. Depending on which two interpretations of JTBD you adhere to, the application, process, and resulting artifacts will look different.

Alan Klement, discussing the mistakes you can make when learning JTBD, emphasizes that JTBD is not a set framework or method: “JTBD is not the study of how people use products, it’s the study of why.”

Where user personas are themselves artifacts (things you could, for instance, put in your portfolio) that result from a process, JTBD is a theoretical approach that helps you to think differently about your product and what it needs to do.

What does JTBD look like in practical terms? The classic example of JTBD looks at a drill. A person goes out and buys a drill. What job is it that they’re hiring that drill to accomplish? They probably don’t just want a drill for the sake of having one (unless they’re a drill collector/connoisseur—is that a thing?). What do they really want? They want for there to be a specific-sized hole in a particular part of their wall, table, or other surface. That is the job to be done.

3. Personas vs. JTBD: Which to use?

Let’s get a better understanding of what these two approaches look like in practice. We’ll use a hypothetical scenario to illustrate both approaches separately.

The Scenario

You’re in the initial stages of designing a mobile meal planning app.Perhaps you’ve got a low- or mid-fidelity prototype, but there’s a long way to go—and right now, anyone involved in the project can have a strong influence the final outcome. You’ve got the concept and the people to help you make it a reality, and you’ve done enough research to know who your users are likely to be.

Approach: User Personas

With a variety of people working on this project, all with varying priorities and perspectives, it’ll take some effort to keep everyone’s vision united and moving the in the same productive direction: meeting user needs. Personas are a great way to keep this vision united. By building users’ actual needs and goals into your personas, you create a measuring stick of sorts that you can use to evaluate the design decisions before they are made.

You do your research and gather information about the kinds of people who are likely to use your meal planning app. What do they need the app for? Do they need it to be integrated with any other apps (one to help make grocery lists, for example)? When are they likely to be using the app? How much information do they want to record in their meal plans? Do they need recipes to be part of this process?

It’s good to think beyond your own assumptions and biases here—embrace the Paradox of Specificity. Design for the needs of a very narrow audience and you’re likely to meet a broader set of needs. Example: The OXO Swivel peeler was originally designed by Sam Farber in an attempt to help his wife, who had arthritis. As it turned out, the design was a big hit and not only for his target user, but for a much broader market.

Your personas tell your team what your users are thinking and feeling and what they’d like to accomplish on your meal planning app. They give specific contextual details that may influence the features you decide to include (or not) and how to organize workflows to ensure that you’re giving your users the information they need, when they need it, and at the right pace. They will even reveal pain points and influence copy and UI elements that come into play later in the process.

Pros:

- Keeps the user front and center

- Puts a face to it all and humanizes the process

- Ideally, represents real user needs and contexts

- Can create empathy and generate buy-in among stakeholders

- Useful throughout the design process (can, for example, help to reveal pain points when you are fine-tuning your app)

Cons:

- Can distract with demographic and emotional details that are not entirely relevant. Does it matter if someone using your meal planning app is 28 or 42? That they are male, female, or any gender identity in between? That they live in Chicago or Berlin? That they are married, engaged, or single?

- Can create an echo chamber of sorts—where your (or your team’s) assumptions about users are reinforced by nature of the fact that you are creating the personas yourself.

- Can result in design choices that exclude some users (based on ability, gender identity, cultural experiences, etc.) if your personas do not adequately or truly take inclusion into account.

Approach: Jobs-to-Be-Done

Taking a truly Jobs-To-Be-Done approach would start before you even decided on a meal planning app. It would begin with the users you want to help. You’d do field studies and interviews and anything else that helps put your hand on the pulse of what your target audience needs. As you do this, you begin to realize that there are a lot of people who express frustration about their eating habits or how much they spend on groceries. You post the question, “How might we help people eat in healthier ways and be smarter in their spending on food?” And eventually you’d reach the idea of a meal planning app.

Maybe you had the meal planning app idea and then backed out of it to make sure you were on track by asking a quintessential JTBD question: What do our users really want?

They probably don’t want just another app on their phone. They want one with this specific function. But why? Do they want to make grocery lists? Maybe. But why? Do they want to try new recipes? Perhaps. But why?

Ultimately, they don’t even want a meal planning app. What they really want is to get better at meal planning—and even this has underlying motivations that are dependent on particular users (ie, to be healthier, to save money, etc.). Knowing this, you can step back and wonder about the ways in which your meal planning app can help create better meal planners!

Pros:

- Reduces bias or echo chamber effects by moving away from who users are, or where they live, or who they do life with and toward what they want to get done

- Useful at the very beginning of the process, when decisions are being made that determine the overall direction and purpose of the app

- Ensures that users will accomplish their goal with your app

- Can generate more inclusive solutions, as long as inherently exclusive assumptions are not made about what users want

Cons:

- Removes the explicitly humanizing elements (particularly the visual ones)

- Still susceptible to assumption

- Less useful throughout the lifespan of the product as it’s not the most useful approach to revealing pain points or determining smaller features and interactions

4. A blended approach to Personas and JTBD

Clearly, these are two very distinct approaches—designers who rely on user personas may feel that JTBD risks a loss of empathy for the end user, and those who prefer JTBD may view user personas as an artifact that misses the point of what actual users really want to accomplish.

But consider for a moment that these two approaches have a common goal: to create a product that actually helps users do what they need to do. And if you look at the pros and cons of each approach, their fundamental compatibility is clear:

JTBD is useful in clarifying end goals, where user personas are useful in building empathy and discovering pain points users encounter when completing a given task on their way to the end goal.

What would it look like to combine the two into a blended approach?

At the beginning of your process, look at the needs of your target users and consider what it is they really want. Do your research on this! Find out what job your users are interested in hiring a product for. Find out what that essential job is—and it’ll likely be something on the level of desire, rather than function.

For example, let’s say we do a lot of interviews and then map out the information we’ve gathered to find that a lot of people seem to want to eat healthier meals and waste less food. So, we ask ourselves, “How might we help people eat healthier and waste less food?” and then go on to brainstorm the many ways that job might get done.

Eventually, we think, “Aha! A meal planning app that integrates list-making and recipe-finding.” Great! We know the job to be done and we have an idea that will get that job done. Now we just need to design a fully functional, aesthetically outstanding, and broadly inclusive app.

Enter user personas. To make sure we don’t accidentally design an app that some potential users simply won’t be able to use or “bake” any assumptions into the design, we’ll develop a full persona spectrum and eliminate any demographic information that isn’t relevant to our product. Using these personas, we can prototype our mealing planning app and then test those prototypes to ensure that we’re designing for users with a range of abilities, identities, backgrounds, and cultural experiences.

At the end of the process, we can return to our JTBD foundation and test the app to make sure that it’s really getting the job done for as many of our users as possible.

Remember: JTBD is useful in clarifying end goals, where user personas are useful in building empathy and discovering pain points users encounter when completing a given task on their way to the end goal.

In the end, if we can stop the battle and embrace the compatible strengths of both approaches, their combined power could have a deep and dynamic effect on the products we choose to design, the quality and usability of those products, and the range of users who are able to put those products to work in their lives.

If you’d like to learn more about user personas and their place in the UX design process, check out these articles: